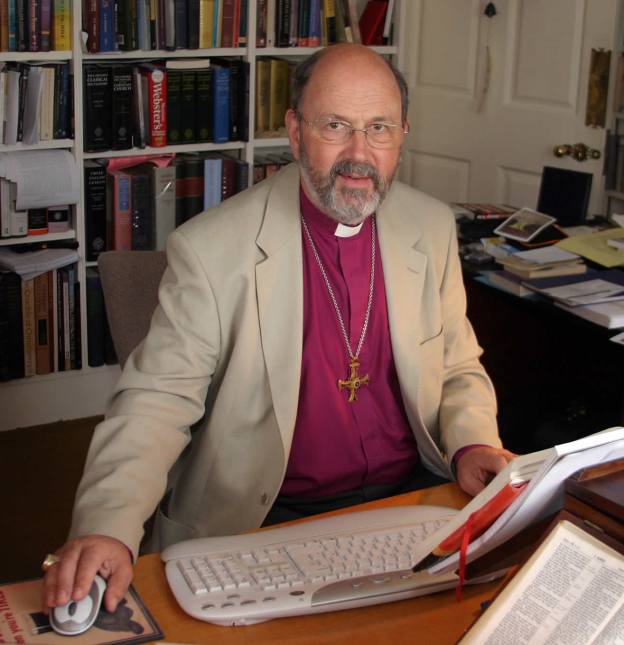

This book review may be a little overdue: I read N.T. Wright’s Surprised by Hope this past November, nearly four months ago. But in the course of Holy Week, I figured this would be an appropriate time to recommend to you a book that is chiefly concerned with the event that Christians will commemorate this upcoming Sunday, the Resurrection of Jesus the Christ.

This book review may be a little overdue: I read N.T. Wright’s Surprised by Hope this past November, nearly four months ago. But in the course of Holy Week, I figured this would be an appropriate time to recommend to you a book that is chiefly concerned with the event that Christians will commemorate this upcoming Sunday, the Resurrection of Jesus the Christ.

We hear the word every day. Hope. We employ it into our conversations so frequently and flippantly that it has almost become synonymous with words like want and wish. With reference to the theme of hope within a Christian context, then, what is actually denoted? This broad query is what Wright sets out to expound in the book. If asked to summarize Surprised by Hope, I might succinctly reply that it is about the anticipation for “life after life after death.” (Such a summation would undoubtedly leave you pondering what on earth life after life after death could possibly mean, and at that time my work would be finished. You would most likely be unable to resist picking it up and thumbing through it.) This phrase, used by Wright throughout the book, implies that there is more to present Christian hope for the future than a disembodied existence in a spiritual realm called Heaven. In fact, if this is what we envision the climax of God’s redemptive plan to be, immortal souls abandoning the sinful flesh of an evil world in order to spend eternity in a perfect, other-worldly location, then our beliefs align more with a kind of Platonism or Gnosticism than they do to Christianity. Wright insists that the New Testament language of the resurrection, the new heavens and the new earth, is to be understood in light of the Kingdom of God being inaugurated on earth through the resurrection of Jesus Christ. This means that Christian hope for God’s new creation, the “new heavens and new earth,” expresses and manifests itself here and now; Christians anticipate God’s promise to renew all things by working for God’s kingdom in the present life. Had Jesus’ action of conquering death in the resurrection not actually occurred, the cross would be a much different symbol; for the paramount implications of the cross lie within the resurrection event and not simply the crucifixion. Good Friday wouldn’t be good at all had Christ not come out of the tomb on Easter. Wright makes this clear throughout.

The model of hope espoused by Wright is not an attempted paradigm shift fabricated in response to the ubiquitous rapture theology that arose in the 20th century. Instead, it is a recapitulation of 1st century Christian hope which has its foundation in Jewish beliefs about death and the afterlife.We commit a serious blunder, Wright thinks, when we try to understand the formation of the Church outside its Jewish context. Early in the book, Wright asserts that what we think of death, and life beyond it, is the key to seriously thinking about everything else. In other words, our conception of death will determine how we think about things in life. If you believe that the world is evil, that Christian hope means waiting for Jesus to run an errand to Earth to gather all of those who believe in him and then ascend back to heaven, thereby leaving non-believers behind to endure an interval of ungodliness until Jesus returns once again to reign forever, then you will see no need in striving for a community of believers committed to working for the Kingdom in the present life.

Summarizing what he sets out in much detail elsewhere, Wright explains how early Christian hope was firmly centered on resurrection – a belief shared with Judaism but not the ancient pagan world (think of the Sadducees). Many pagans believed in life after death, but the two-step belief about the future – first, death followed by whatever lies immediately subsequent to it; second, new bodily existence in a remade word – was specific to Jews. The Christian beliefs about death and the resurrection of the body are modifications of the Jewish beliefs, based on the bodily resurrection of Jesus. “Christ has been raised from the dead, the first fruits of those who have died” (1 Cor 15.20). What the Father accomplishes in the Son on Easter is an inauguration of what God will eventually do for us in his new creation.

With regard to the present implications of Christ’s resurrection, Wright says, “Our task in the present…is to live as resurrection people in between Easter and the final day, with our Christian life, corporate and individual, in both worship and mission, as a sign of the first and a foretaste of the second.” Our hope for God’s new creation, wherein God will bring heaven and earth together, provides the Church with a telos, an end, that does not simply amount to “saving souls” or, as he says, “making life better within the continuation of the world as it is.” Our deeds of love, compassion, humility and forgiveness serve as signposts for what is to be expected in God’s new world. If our hope rests in the anticipation of God’s fulfillment in his creation, then we will act in confidence, knowing that what we do in Christ “is not in vain” (1 Cor 15:58). A proper view of biblical eschatology demands us to take part in the work of God’s kingdom now.

When our faith centers on the hope of the resurrection, we might be surprised by the present results.